HDL Cholesterol and HDL Particle: Diagnostic Significance and Clinical Insights

Authors: Payal Bhandari M.D, Tejal, Madison Granados

Contributors: Vivi Chador, Amer Džanković, Hailey Chin

|

|

Key Insights

Cholesterol is a fat that helps make hormones, vitamin D, and bile, mostly produced by the liver and some organs, with a small amount from food. It travels in the blood via protein carriers called lipoproteins: VLDL, LDL, and HDL. More protein means less fat. Too much LDL and VLDL, with low HDL, raises the risk of heart disease, diabetes, and organ damage. Monitoring HDL helps assess risk, and managing cholesterol through hydration, diet, exercise, stress control, and medication can prevent serious health issues.

What Is HDL Cholesterol?

HDL cholesterol is part of a lipid panel, a blood test measuring total cholesterol, including LDL, HDL, VLDL, and triglycerides. HDL is “good” cholesterol, helping prevent clogged arteries, inflammation, and organ damage. Lipids include phospholipids, sterols, fatty acids, and the main type of fat, triglycerides. Saturated fats have straight chains, while unsaturated fats have at least one double bond, creating a bent shape.

Figure 1: Lipid (Cholesterol) structure is present in all cellular membranes and lipoproteins.

Figure 2: Lipoproteins have a core of cholesterol esters and triglycerides, surrounded by free cholesterol, phospholipids, and apoproteins, which aid their formation and function1.

Figure 3: Lipoproteins transport cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood, including chylomicrons, VLDL, IDL, LDL, HDL, and Lp(a). LDL, VLDL, and Lp(a) raise heart disease risk, while HDL offers protection. Since fats can’t dissolve in water, they bind to apolipoproteins, which help form lipoproteins and regulate fat breakdown.

What are HDL Particles (HDL-P)?

HDL-P predicts artery inflammation better than standard HDL tests by measuring particle size, number, and composition via NMR spectroscopy or ion mobility analysis. Higher HDL-P reduces LDL oxidation and inflammation, while lower levels increase tissue damage. Larger, lighter HDL particles provide better heart protection than smaller, denser ones.

Cholesterol Synthesis

The body produces most cholesterol, with a small portion from food like dairy, meat, eggs, fish, oils, and nuts. About 20–25% is made in the liver, while the rest comes from the intestines, adrenal glands, and reproductive organs, requiring energy-intensive cellular reactions.

The body makes cholesterol from Acetyl-CoA, which comes from carbs, fats, and proteins. Acetyl-CoA first turns into HMG-CoA with the help of an enzyme called HMG-CoA synthase. Cholesterol levels help control this process.

HMG-CoA is then converted into mevalonate by HMG-CoA reductase, the slowest step in cholesterol production. Statin drugs lower cholesterol by blocking this enzyme.

Mevalonate goes through several steps to form building blocks called IPP and DMAPP, which are essential for making cholesterol. These combine to form a larger molecule called squalene.

Squalene then turns into lanosterol, which eventually becomes cholesterol with the help of several enzymes

Figure 4: De-Novo Cholesterol Synthesis

HDL Cholesterol Formation

Nascent HDL forms through reverse cholesterol transport in the liver and intestine. Small HDL binds to apoprotein A1, making it water-soluble, then collects excess fats like triglycerides, VLDL, and LDL in the blood. It delivers them to the liver, preventing LDL buildup in arteries and reducing inflammation. Higher HDL levels protect against disease, while low levels increase atherosclerosis and autoimmune risks.

Figure 5: Reverse cholesterol transport creates mature HDL. The liver and intestine produce ApoA-1, HDL, and phospholipids, releasing them into the blood. The enzyme ABCA1 helps ApoA-1 bind to HDL, allowing it to transport cholesterol to the liver and lower harmful cholesterol, reducing inflammation and atherosclerosis risk.

Regulation of Cholesterol Synthesis

Cholesterol metabolism in the peripheral and central nervous systems is regulated separately by the blood-brain barrier. Peripheral metabolism balances dietary intake, liver synthesis, and cholesterol excretion. In contrast, the central nervous system relies solely on liver synthesis for proper brain function.

Peripheral Tissue Cholesterol Synthesis

Peripheral cholesterol synthesis is less regulated than the liver, which responds to dietary, hormonal, and physiological factors. About 9 mg/kg body weight is synthesized daily, with 600–800 mg transported to the liver for metabolism and excretion via reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), regulated by transcription factors, receptors, and enzymes6:

SREBPs (Sterol Regulatory Element-Binding Proteins)

SREBPs help make cholesterol and fatty acids when cell cholesterol is low.LDLRs (Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptors)

These receptors pull LDL (“bad” cholesterol) into cells. Too much LDL in the blood reduces the number of these receptors.LXRs (Liver X Receptors)

LXRs help remove cholesterol from cells and send it to the liver for disposal. Oxysterols (oxidized cholesterol) activate LXRs, which work with RXRs (Retinoid X Receptors) to turn on cholesterol-clearing genes.

De Novo Cholesterol Synthesis in the Liver

Liver cholesterol synthesis is regulated by dietary, hormonal, and physiological factors involved in energy production (ATP). Food breaks down into glucose, fatty acids (FAs), and amino acids (AAs), with glucose mainly fueling ATP. Insulin moves glucose into tissues for energy. Excess undigested food is then transported to the liver, and undergoes the following cascade of reactions:

Glucose is converted into glycogen and then either to FA’s or AA’s.

FAs are converted to triacylglycerol (TAG), which is either stored in the liver or sent into the blood as very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL).

Proteins and AAs are broken down for ATP or reused to build new proteins.

When fasting, exercising intensely, or in diabetes (insulin imbalance), the body uses FAs and proteins for energy instead of glucose. The brain can’t use FAs directly, so triglycerides break down into glucose. This process releases hormones like glucagon and catecholamines, reducing insulin levels. Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) then breaks down fat and glycogen, producing ketones for energy. HMG-CoA synthase creates acetoacetate, which HMG-CoA lyase converts into beta-hydroxybutyrate for fuel. Some acetoacetate turns into acetone and is exhaled. .

During fasting or intense exercise, the liver releases VLDL cholesterol, and adipose tissue breaks down NEFAs and glycerol. Muscles degrade proteins, releasing lactate and alanine into circulation. The liver then turns VLDL and NEFAs into ketones and uses amino acids, lactate, and glycerol to make glucose.

Figure 6: Circadian rhythm genes regulate liver glucose and ketone synthesis, optimizing energy use from fats, amino acids, and glycerol. Increased ketones stabilize blood sugar, enhance insulin and leptin sensitivity, and reduce brain dependence on carbs and proteins, lowering hunger, stress hormones, and inflammation.

Regulation of HDL Cholesterol Metabolism

Peripheral and central HDL metabolism are separated by the blood-brain barrier and function independently. Peripheral metabolism balances dietary intake, liver synthesis, and cholesterol excretion, while the brain relies solely on liver-derived cholesterol.

Glucagon interacts with lipoprotein lipase (LPL) to break down triglycerides (TG) into free fatty acids (FFA), which bind to albumin for transport to muscles and organs for energy or storage.

The exogenous pathway: LPL packages dietary TG into chylomicrons, mixing them with bile acids, cholesterol, and fat-soluble vitamins. A healthy liver efficiently processes up to 100g of fat daily without significantly raising TG, VLDL, or LDL levels.

The endogenous pathway: The liver metabolizes TG in VLDL, shrinking them into intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL), which convert to LDL after binding to LDL receptors. Lower-density lipoproteins contain more fat and less protein.

In the small intestine, most FFAs come from dietary fat, while cholesterol mainly derives from bile salts (800–1200 mg vs. 200–500 mg from diet).Chylomicron (CM) size depends on fat intake—higher fat consumption leads to larger CMs, increasing fatty acid transport to the liver for VLDL and LDL synthesis. During fasting, FAs fuel energy, reducing TG supply, apoprotein A production, and the formation of IDL and LDL.

After a meal, VLDL triglycerides originate from plasma FFA (44%), diet-derived FFA (10%), CM remnants (15%), and de novo lipogenesis (8%). During fasting, plasma FFA contributes 77%, while de novo lipogenesis drops to 4%.

Figure 7: Exogenous and Endogenous Pathways for Dietary Fat Metabolism and Cholesterol Synthesis. Dietary fat turns into chylomicrons (CM), which deliver nutrients to muscles and fat cells. As CM shrink, they transfer parts to HDL. CM remnants then go to the liver, helping make VLDL and bile acids.

Figure 8: Cholesterol Synthesis and Regulation. Acetyl CoA undergoes enzyme-driven reactions to form cholesterol, which is then used to produce steroid hormones, bile salts, vitamin D, oxysterols, lipoproteins, and cell membranes.

Role of Cholesterol in the Body

Cholesterol maintains cell structure, fluidity, and signaling while supporting skin, hair, temperature regulation, and organ insulation. It prevents lipid packing in cold temperatures and reduces membrane fluidity in heat. It also helps synthesize steroid hormones, vitamin D, bile acids, and aids in lipid digestion and energy use.

Figure 9: The cell membrane is a lipid-protein mosaic, with polar phospholipid heads facing outward and nonpolar tails inward, creating a selective barrier. Small nonpolar molecules like CO₂ pass freely, while large polar ones like glucose need transport proteins. Embedded proteins aid structure, transport, and signaling. Cholesterol and tail saturation regulate membrane fluidity, crucial for cell movement and stress response.

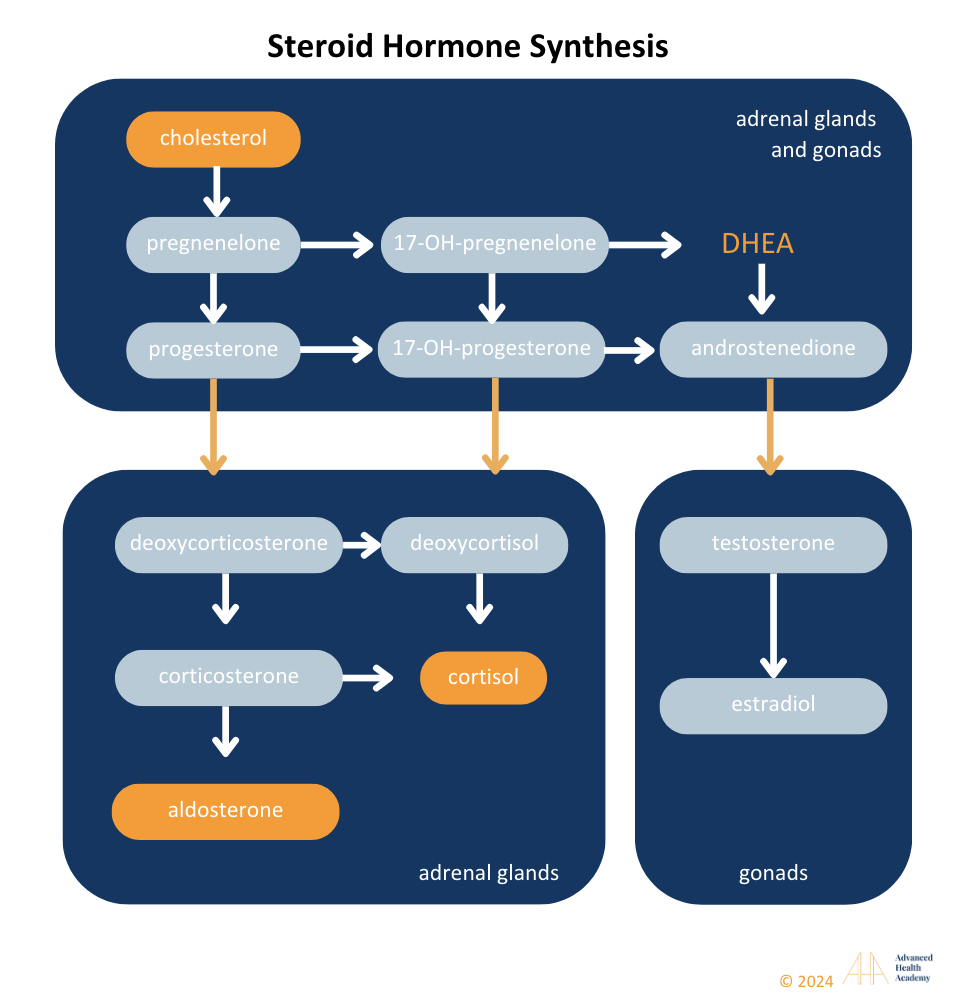

Cholesterol is an Integral Part of Synthesizing All Steroid Hormones

Figure 10: Liver cytochrome P450 enzymes convert cholesterol into steroid hormones, including mineralocorticoids (aldosterone), glucocorticoids (cortisol), androgens (testosterone, progesterone, estradiol), and DHEA. Defects can disrupt pathways, leading to hormonal disorders like PCOS or hypogonadism. High cholesterol may increase aldosterone, cortisol, and estradiol while lowering DHEA and testosterone.

Cholesterol is the Precursor for Bile Salt Production

Bile acids are made in the liver and are mostly organic. They contain cholesterol and phospholipids. Bile salts help digest fats, carry vitamins (A, D, E, K), and remove extra cholesterol. They also protect cells from damage caused by oxidation.

Cholesterol is the Precursor for vitamin D Production

Vitamin D is a key nutrient that acts like a hormone in the body. There are two main types:

Vitamin D2 – found in plants and yeast

Vitamin D3 – found in animal products

The body also makes vitamin D3 when the skin is exposed to sunlight. UV rays turn cholesterol in the skin into vitamin D3, which the liver and kidneys convert into an active form the body can use.

Cholesterol is an Antioxidant

Figure 11: Oxidized cholesterol (oxysterols) activates Liver X receptors (LXRs), aiding LDL removal to the liver and spleen for breakdown and supporting steroid hormone synthesis. Low oxysterols trigger SREBPs to increase LDL production, while excess oxysterols inhibit this process, leading to storage in bile or excretion .

Oxysterols are altered forms of cholesterol made through oxidation. They protect tissues from oxidative stress by acting as antioxidants and also store toxins in fat until removal via stool, urine, sweat, sebum, blood, or hair growth.

Clinical Significance of Monitoring HDL Cholesterol and HDL-Particle Levels 5

Figure 12: Extremely low cholesterol can cause multi-organ damage, hormonal imbalances, infections, cancer, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, diabetes, and vascular diseases.

Hyperlipidemia, or high blood fat levels, often results from poor lifestyle choices, affecting fat metabolism and energy use. It involves high TG, VLDL, and LDL, with low HDL. In contrast, high HDL, especially large particles, supports hormonal balance and is generally not a concern.

Extremely low HDL is linked to dysbiosis and reduced blood flow to organs. Gut microbiota aids digestion, nutrient absorption, and waste excretion. Slow stomach emptying reduces healthy bacteria, contributing to dysbiosis .

Figure 13: Healthy gut microbiota maintains energy, hormonal, and metabolic balance by aiding digestion, nutrient absorption, and waste excretion. Dysbiosis, or reduced beneficial bacteria, disrupts metabolism and increases pathogens, cancer cells, and immune dysfunction.

Dysbiosis disrupts metabolism, protein and vitamin synthesis, and nutrient absorption, leading to undigested food particles in the blood, increased viscosity, and reduced oxygen delivery. The liver compensates by storing excess fat in VLDL and organs, increasing oxidative stress (ROS) and inflammation . This triggers white blood cells to clear waste instead of fighting pathogens, contributing to autoimmune disorders, infections, and vascular diseases. Dyslipidemia, even after adjusting for health factors, raises the risk of metabolic and endocrine disorders, hormonal imbalances, and organ damage.

The consequences of low HDL cholesterol levels include, but are not limited to the following diseases:

Liver Dysfunction and Damage

Figure 14: The liver regulates cholesterol, protein metabolism, and detoxification. Dysfunction leads to excess inflammatory cholesterol, depriving organs of nutrients and oxygen. Chronic inflammation (dyslipidemia) can cause steatohepatitis, fibrosis, or cirrhosis.

Dysregulated Hormonal and Energy Balance and Atherosclerosis-Induced Vascular Diseases

A high-cholesterol dietLDL cholesterol by increasing its receptors on liver cells, helping remove LDL from the blood. This diet also raises levels of certain hormones, including luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). LH helps the ovaries produce androgens, FSH supports follicle and estrogen production, and TSH stimulates the thyroid to release thyroid hormones (T3 and T4), which increase energy use (hyperthyroidism).

Too many androgens (as in PCOS) or long-term hormone therapy can disrupt ovulation and increase cholesterol production while lowering “good” HDL cholesterol. This leads to excess “bad” LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, which clog arteries and reduce blood flow. White blood cells absorb this cholesterol, causing inflammation and plaque buildup (atherosclerosis). This process raises blood sugar, increases fat storage (mainly in the abdomen), and worsens insulin resistance. Studies show losing 5–10% of body weight can improve insulin levels and reduce PCOS symptoms.

Figure 15: Atherosclerosis-induced inflammation causes fat and scar buildup in arteries, excess clotting, and restricted blood flow, raising blood pressure and affecting organs like the liver, heart, and pancreas. Overactive white blood cells and platelets disrupt immunity, aiding tumor cells and pathogens in tissue clearance, bleeding prevention, and wound repair .

Short-term thyroid hormone use boosts fat metabolism, energy, and HDL, but long-term use or dysfunction can increase atherosclerosis risk. Excess carb-to-fat conversion lowers HDL, raising TG-rich VLDL and LDL, disrupting immunity. A Chinese study found high cholesterol (>200 mg/dL) raised hypothyroidism risk 6–15 times over three years. Statins may improve remission rates .

High-cholesterol animal diets can reduce testosterone by downregulating key enzymes (StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD) and inhibiting Leydig cell sensitivity to LH. Angiotensin 3 and 4 further block testosterone production . In contrast, a plant-rich diet lowers atherogenic cholesterol and supports steroid pathways, boosting testosterone.

Autoimmune Disorders

Autoimmune diseases like RA, SLE, IBD, and MS are linked to atherosclerosis-induced vascular inflammation . A meta-analysis of 24 studies (111,758 patients) found RA increases vascular death risk by 50%, with cardiovascular risk similar to diabetes . Autoimmune-related lipid abnormalities 137 include low HDL and apolipoprotein A-I, high triglycerides and lipoprotein (a), and decreased total and LDL cholesterol in severe cases.

Chronic Kidney Dysfunction and Damage

Studies show high-cholesterol animal diets lower HDL and increase kidney atherogenic deposits, raising CKD risk 55. A 2020 Zhejiang study linked high triglycerides, total cholesterol, and LDL to lower eGFR and higher CKD incidence due to fatty acids and oxidative stress damaging kidneys . Lowering TG-rich VLDL and LDL while increasing HDL can help. A meta-analysis of 59 trials found statins slowed eGFR decline. Since CKD patients are vulnerable to medication-related kidney damage, a plant-based, oil-free diet offers significant benefits.

Skin Disorders

Excess cholesterol on the skin triggers sebum production, altering microbiota and allowing bacteria like P. acnes to colonize, leading to acne and autoimmune skin disorders (e.g., psoriasis, pemphigus, xanthomas). Many acne sufferers have low HDL, high LDL, and elevated androgens, increasing metabolic and gonadal dysfunction risks. Excess androgens worsen acne, promote atherosclerosis, and cause hirsutism or alopecia128. The skin uses cholesterol to produce steroid hormones, including DHT, which, along with oxysterols, can accelerate scalp hair loss.

Infections

Cholesterol is key to cell membranes, but excess LDL damages cells, aiding pathogen binding and infection progression . Severe infections correlate with lower total cholesterol, HDL, and apolipoprotein A-I, predicting mortality . Infections worsen metabolic conditions by increasing glucose production, reducing fat metabolism, and causing obesity, leading to inflammation and immune overactivation, which accelerates vascular damage, raises blood pressure, and impairs organ function. The lipid abnormalities associated with various infections typically involves137:

Decrease in HDL-cholesterol and apolipoprotein A-I

Elevated serum triglyceride and lipoprotein (a) levels

Decreasing total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol

Lowering LDL and boosting HDL may reduce infection risks like COVID-19 . However, severe infections can drastically lower HDL and LDL due to liver injury, inflammation, and oxidative stress, leading to hypoxia and impaired energy production.

Cancer Growth and Metastasis

Many studies have shown that various cancers are associated with reduced HDL cholesterol synthesis and excess triglyceride-rich VLDL and LDL cholesterol in the circulation that are ingested by tumor cells, thereby enhancing cancer growth and metastasis48. Extremely high and severely low 25-hydroxycholesterol levels are associated with lower survival rates. The following cancers have a direct correlation with reduced HDL synthesis: pancreatic cancer , colon cancer , breast cancer (especially in overweight and obese individuals) , prostate cancer , liver cancer , lung cancer , ovarian cancer , and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) .

Figure 16: Low HDL increases atherogenic cholesterol, inflammation, and cancer risk. Oxidative stress damages vessels, allowing cholesterol buildup. Tumor cells bind to arteries, trigger inflammation, and interact with platelets and neutrophils, promoting clotting, angiogenesis, and immune evasion, fueling cancer growth.

Brain and Nerve Damage

The brain has high cholesterol but must synthesize its own due to the blood-brain barrier . Metabolic disorders like diabetes and obesity reduce fat metabolism and HDL, increasing ROS, which damages the brain and nerves . White blood cells and platelets infiltrate to repair damage, diverting energy from clearing inflammatory proteins like beta-amyloid . This chronic inflammation boosts cholesterol synthesis, mitochondrial activity, and ROS, impairing neurons and contributing to neurodegenerative diseases. A diet high in saturated fat and protein, which lowers HDL, can accelerate these conditions :

Learning disabilities

Cerebrovascular dysfunction

Mild cognitive impairment (familial hypercholesterolemia)

Cognitive impairment with impaired blood-brain barrier and neuroinflammation (such as dementia 169 )

Depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders

Prevalence and Statistics of Low HDL Cholesterol and High Small, Dense HDL Particle Levels

Low HDL and large HDL particles, along with high small, dense HDL particles, raise the risk of atherosclerosis, autoimmune disorders, infections, cancer, and organ damage. This condition, linked to excess atherogenic cholesterol, causes an estimated 2.6 million deaths (4.5% of total) and 29.7 million DALYs (2% globally).

Hypercholesterolemia is a major global health issue, with 39% of adults having high cholesterol in 2008. Prevalence was highest in Europe (54%) and the Americas (48%), where diets are rich in animal protein, while Africa (22.6%) and Southeast Asia (29%) had lower rates due to plant-based diets. Cholesterol levels also rose with income; over 50% of adults in high-income countries had elevated cholesterol, compared to 25% in low-income nations 51.

A 2018–2020 Global Diagnostics Network study of 461 million lipid results across 17 countries found total cholesterol and LDL levels peaked in women at 50–59 years and men at 40–49 years 185. Countries above the mean included Japan, Australia, and several in Europe. Cholesterol levels varied by region, gender, lifestyle, genetics, testing, and treatment .

Figure 17: A 2018–2020 study of cholesterol levels across 17 countries highlights dyslipidemia as a global issue. High total and LDL cholesterol correlate with diets rich in animal products or food poverty. The data underscores the need to address social and economic factors driving hyperlipidemia.

Conclusion

Managing dyslipidemia involves lifestyle changes like a plant-forward diet, exercise, fasting, stress management, avoiding tobacco and alcohol, addressing medication effects, and maintaining a healthy weight. Medication may help short-term until habits improve. Since lipid profiles alone don’t fully indicate health risks, monitoring apoproteins and lipoprotein size can guide treatment. Family history, age, gender, and other conditions also influence risk, requiring a comprehensive approach.

Source References and Supplemental Research:

Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, et al. Introduction to Lipids and Lipoproteins. MDText.com, Inc.; 2000. www.endotext.org

Chait A, Ginsberg HN, Vaisar T, Heinecke JW, Goldberg IJ, Bornfeldt KE. Remnants of the Triglyceride-Rich Lipoproteins, Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease. Diabetes 2020; 69:508-516 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Krauss RM, King SM. Remnant lipoprotein particles and cardiovascular disease risk. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2023; 37:101682 [PubMed]

Berneis KK, Krauss RM. Metabolic origins and clinical significance of LDL heterogeneity. J Lipid Res 2002; 43:1363-1379 [PubMed]

Asztalos BF, Niisuke K, Horvath KV. High-density lipoprotein: our elusive friend. Curr Opin Lipidol 2019; 30:314-319 [PubMed]

Thakkar H, Vincent V, Sen A, Singh A, Roy A. Changing Perspectives on HDL: From Simple Quantity Measurements to Functional Quality Assessment. J Lipids 2021; 2021:5585521 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Thomas SR, Zhang Y, Rye KA. The pleiotropic effects of high-density lipoproteins and apolipoprotein A-I. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2023; 37:101689 [PubMed]

Julve J, Martin-Campos JM, Escola-Gil JC, Blanco-Vaca F. Chylomicrons: Advances in biology, pathology, laboratory testing, and therapeutics. Clin Chim Acta 2016; 455:134-148 [PubMed]

Daoud E, Scheede-Bergdahl C, Bergdahl A. Effects of Dietary Macronutrients on Plasma Lipid Levels and the Consequence for Cardiovascular Disease. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2014; 1:201-213. 10.3390/jcdd1030201.

Gerber PA, Nikolic D, Rizzo M. Small, dense LDL: an update. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2017 Jul;32(4):454-459. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000410. PMID: 28426445.

Thomas A. B. Sanders (2016): “The Role of Fats in Human Diet.” Pages 1-20 of Functional Dietary Lipids. Woodhead/Elsevier, 332 pages. ISBN 978-1-78242-247-1doi:10.1016/B978-1-78242-247-1.00001-6

Entry for “fat” Archived 2020-07-25 at the Wayback Machine in the online Merriam-Webster dictionary, sense 3.2. Accessed on 2020-08-09

Wu, Yang; Zhang, Aijun; Hamilton, Dale J.; Deng, Tuo (2017). “Epicardial Fat in the Maintenance of Cardiovascular Health.” Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal. 13 (1): 20–24. doi:10.14797/mdcj-13-1-20. ISSN 1947-6094. PMC 5385790. PMID 28413578.

Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. Lipids: a key player in the battle between the host and microorganisms. J Lipid Res 2012; 53:2487-2489 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

White, Hayden; Venkatesh, Balasubramanian (2011). “Clinical review: Ketones and brain injury.” Critical Care. 15 (2): 219. doi:10.1186/cc10020. PMC 3219306. PMID 21489321

Abumrad NA, Davidson NO. Role of the gut in lipid homeostasis. Physiol Rev 2012; 92:1061-1085 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Olivecrona G. Role of lipoprotein lipase in lipid metabolism. Curr Opin Lipidol 2016; 27:233-241 [PubMed]

Dallinga-Thie GM, Franssen R, Mooij HL, Visser ME, Hassing HC, Peelman F, Kastelein JJ, Peterfy M, Nieuwdorp M. The metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins revisited: new players, new insight. Atherosclerosis 2010; 211:1-8 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

M. Adiels, S.O. Olofsson, M.R. Taskinen, et al., Overproduction of very low-density lipoproteins is the hallmark of dyslipidemia in the metabolic syndrome, Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, Vasc. Biol. 28 (2008) 1225e1236.

Hooper AJ, Burnett JR, Watts GF. Contemporary aspects of the biology and therapeutic regulation of the microsomal triglyceride transfer protein. Circ Res 2015; 116:193-205 [PubMed] [Reference list]

S. Tiwari, S.A. Siddiqi, Intracellular trafficking and secretion of VLDL, Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, Vasc. Biol. 32 (2012) 1079e1086. DOI: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241471

Daoud E, Scheede-Bergdahl C, Bergdahl A. Effects of Dietary Macronutrients on Plasma Lipid Levels and the Consequence for Cardiovascular Disease. Journal of Cardiovascular Development and Disease. 2014; 1:201-213. 10.3390/jcdd1030201.

Espenshade, P.J. SREBPs: sterol-regulated transcription factors. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 973-976.

Dawidowicz, E.A. Dynamics of membrane lipid metabolism and turnover. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1987, 56, 43–61.

Wang, H.H.; Garruti, G.; Liu, M.; Portincasa, P.; Wang, D.Q.-H. Cholesterol and Lipoprotein Metabolism and Atherosclerosis: Recent Advances in Reverse Cholesterol Transport. Ann. Hepatol. 2017, 16 (Suppl. S1), S27–S42.

Sacks, F.M.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Wu, J.H.; Appel, L.J.; Creager, M.A.; Kris-Etherton, P.M.; Miller, M.; Rimm, E.B.; Rudel, L.L.; Robinson, J.G. and Stone, N.J. Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017, 136, e1–e23.

Di Ciaula, A.; Garruti, G.; Baccetto, R.L.; Molina-Molina, E.; Bonfrate, L.; Portincasa, P.; Wang, D.Q.. Bile acid physiology. Ann. Hepatol. 2017, 16, s4–s14.

Cox, R.A.; García-Palmieri, M.R. Cholesterol, Triglycerides, and Associated Lipoproteins. In Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations; Walker, H.K., Hall, W.D., Hurst, J.W., Eds.; Butterworths: Boston, MA, USA, 2011.

Piskin E, Cianciosi D, Gulec S, Tomas M, Capanoglu E. Iron Absorption: Factors, Limitations, and Improvement Methods. ACS Omega. 2022 Jun 21; 7(24): 20441–20456. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c01833

Benkhedda K.; L’abbé M. R.; Cockell K. A. Effect of Calcium on Iron Absorption in Women with Marginal Iron Status. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103 (5), 742–748. 10.1017/S0007114509992418.

Ziegler E.E. Consumption of cow’s milk as a cause of iron deficiency in infants and toddlers. Nutr. Rev. 2011;69:37–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00431.x.

Bondi S.A., Lieuw K. Excessive Cow’s Milk Consumption and Iron Deficiency in Toddlers, Two Unusual Presentations and Review. ICAN Infant Child Adolesc. Nutr. 2009;1:133–139. doi: 10.1177/1941406409335481. [CrossRef]

Gifford GE, Duckworth DH. Introduction to TNF and related lymphokines. Biotherapy. 1991;3:103–111

De Chiara, F., Checcllo, C. U., & Azcón, J. R. (2019). High protein diet and metabolic plasticity in Non-Alcoholic Fatty liver Disease: Myths and Truths. Nutrients, 11(12), 2985. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11122985 [PubMed]

Esse, R.; Barroso, M.; Almeida, I.; Castro, R. The contribution of homocysteine metabolism disruption to endothelial dysfunction: State-of-the-art. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version].

Kruman, I.I.; Culmsee, C.; Chan, S.L.; Kruman, Y.; Guo, Z.; Penix, L.; Mattson, M.P. Homocysteine elicits a DNA damage response in neurons that promotes apoptosis and hypersensitivity to excitotoxicity. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 6920–6926.

Guoyao Wu; Yun-Zhong Fang; Sheng Yang; Joanne R. Lupton; Nancy D. Turner (2004). “Glutathione Metabolism and its Implications for Health”. Journal of Nutrition. 134 (3): 489–492. doi:10.1093/jn/134.3.489. PMID 14988435 [PubMed]

Pompella A, Visvikis A, Paolicchi A, De Tata V, Casini AF (October 2003). “The changing faces of glutathione, a cellular protagonist”. Biochemical Pharmacology. 66 (8): 1499–1503. doi:10.1016/S0006-2952(03)00504-5. PMID 14555227

S. Tiwari, S.A. Siddiqi, Intracellular trafficking and secretion of VLDL, Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, Vasc. Biol. 32 (2012) 1079e1086. DOI: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.241471

Reichert CO, Levy D, Bydlowski SP. Paraoxonase Role in Human Neurodegenerative Diseases. Antioxidants (Basel). 2020 Dec 24;10(1):11. doi: 10.3390/antiox10010011. PMID: 33374313; PMCID: PMC7824310.

Sengupta, S.; Chen, H.; Togawa, T.; DiBello, P.M.; Majors, A.K.; Büdy, B.; Ketterer, M.E.; Jacobsen, D.W. Albumin thiolate anion is an intermediate in the formation of albumin-S-S-homocysteine. J. Biol Chem. 2001, 276, 30111–30117.

Diamond, J.R. Analogous Pathobiologic Mechanism in Glomerulosclerosis and Atherosclerosis. Kidney Int. 1991, 31, 29–34.

Chen, P.; Poddar, R.; Tipa, E.V.; Dibello, P.M.; Moraveca, C.D.; Robinson, K.; Green, R.; Kruger, W.D.; Garrow, T.A.; Jacobsen, D.W. Homocysteine Metabolism in Cardiovascular Cells and Tissues: Implication for Hyperhomocysteinemia and Cardiovascular Disease. Adv. Enzym. Regul. 1999, 39, 93–109.

Ho, P.I.; Ashline, D.; Dhitavat, S.; Ortiz, D.; Collins, S.C.; Shea, T.B.; Rogers, E. Folate deprivation induces neurodegeneration: Roles of oxidative stress and increased homocysteine. Neurobiol. Dis. 2003, 14, 32–42.

M.B. Fessler, The challenges and promise of targeting the Liver X Receptors for treatment of inflammatory disease, Pharmacol. Ther. (2017), https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2017.07.010 pii: S0163-7258(17)30190-0.

S.D. Lee, P. Tontonoz, Liver X receptors at the intersection of lipid metabolism and atherogenesis, Atherosclerosis 242 (2015) 29e36.

D.S. Green, H.A. Young, J.C. Valencia, Current prospects of type II interferon gamma signaling and autoimmunity, J. Biol. Chem. 292 (2017) 13925e13933.

M. Buttet, H. Poirier, V. Traynard, et al., Deregulated lipid sensing by intestinal CD36 in diet-induced hyperinsulinemic obese mouse model, PLoS One 11 (2016), e0145626.

Main, P.A.; Angley, M.T.; O’Doherty, C.E.; Thomas, P.; Fenech, M. The potential role of the antioxidant and detoxification properties of glutathione in autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Desai, A.; Sequeira, J.M.; Quadros, E.V. The metabolic basis for developmental disorders due to defective folate transport. Biochimie 2016, 126, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ali, A.; Waly, M.I.; Al-Farsi, Y.M.; Essa, M.M.; Al-Sharbati, M.M.; Deth, R.C. Hyperhomocysteinemia among Omani autistic children: A case-control study. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2011, 58, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Al-Farsi, Y.M.; Waly, M.I.; Deth, R.C.; Al-Sharbati, M.M.; Al-Shafaee, M.; Al-Farsi, O.; Al-Khaduri, M.M. Low folate and vitamin B12 nourishment is common in Omani children with newly diagnosed autism. Nutrition 2013, 29, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fuentes-Albero, M.; Cauli, O. Homocysteine Levels in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Clinical Update. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2018, 18, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Altun, H.; Kurutaş, E.B.; Şahin, N.; Güngör, O.; Findikli, E. The Levels of Vitamin D, Vitamin D Receptor, Homocysteine and Complex B Vitamin in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2018, 16, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kałużna-Czaplińska, J.; Żurawicz, E.; Michalska, M.; Rynkowski, J. A focus on homocysteine in autism. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2013, 60, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Mattson, M.P.; Shea, T.B. Folate and homocysteine metabolism in neural plasticity and neurodegenerative disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2003, 26, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ho, P.I.; Ortiz, D.; Rogers, E.; Shea, T.B. Multiple aspects of homocysteine neurotoxicity: Glutamate excitotoxicity, kinase hyperactivation and DNA damage. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002, 70, 694–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Fulceri, F.; Morelli, M.; Santocchi, E.; Cena, H.; Del Bianco, T.; Narzisi, A.; Calderoni, S.; Muratori, F. Gastrointestinal symptoms and behavioral problems in preschoolers with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Dig. Liver Dis. 2016, 48, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chauhan, A.; Audhya, T.; Chauhan, V. Brain region-specific glutathione redox imbalance in autism. Neurochem. Res. 2012, 37, 1681–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rossignol, D.A.; Frye, R.E. Evidence linking oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammation in the brain of individuals with autism. Front. Physiol. 2014, 5, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Frye, R.E.; Melnyk, S.; Fuchs, G.; Reid, T.; Jernigan, S.; Pavliv, O.; Hubanks, A.; Gaylor, D.W.; Walters, L.; James, S.J. Effectiveness of methylcobalamin and folinic acid treatment on adaptive behavior in children with autistic disorder is related to glutathione redox status. Autism Res. Treat. 2013, 2013, 609705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sun, C.; Zou, M.; Zhao, D.; Xia, W.; Wu, L. Efficacy of Folic Acid Supplementation in Autistic Children Participating in Structured Teaching: An Open-Label Trial. Nutrients 2016, 8, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Bottiglieri, T. Folate, vitamin B12, and neuropsychiatric disorders. Nutr. Rev. 1996, 54, 382–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Ezzaher, A.; Mouhamed, D.H.; Mechri, A.; Omezzine, A.; Neffati, F.; Douki, W.; Bouslama, A.; Gaha, L.; Najjar, M.F. Hyperhomocysteinemia in Tunisian bipolarI patients. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011, 65, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kim, H.; Lee, K.J. Serum homocysteine levels are correlated with behavioral and psychological symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2014, 10, 1887–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Altun, H.; Şahin, N.; Belge Kurutaş, E.; Güngör, O. Homocysteine, Pyridoxine, Folate and Vitamin B12 Levels in Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Psychiatr. Danub. 2018, 30, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Brunzell J, Rohlfing J. The Effects of Diuretics and Adrenergic-Blocking Agents on Plasma Lipids. West J Med. 1986 Aug; 145(2): 210–218. PMC1306877

Wolinsky H. The effects of beta-adrenergic blocking agents on blood lipid levels. Clin Cardiol. 1987 Oct;10(10):561-6. Doi: 10.1002/clc.4960101010

Stocker R, Yamamoto Y, McDonagh AF, Glazer AN, Ames BN. Bilirubin is an antioxidant of possible physiological importance. Science. 1987;235(4792):1043-6.

Baranano DE, Rao M, Ferris CD, Snyder SH. Biliverdin reductase: a major physiologic cytoprotectant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(25):16093-8.

B.R. Barrows, E.J. Parks, Contributions of different fatty acid sources to very low-density lipoprotein-triacylglycerol in the fasted and fed states, J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metabolism 91 (2006) 1446e1452. DOI: 10.1210/jc.2005-1709